Python Ecosystem for EO#

Core Python Libraries Overview#

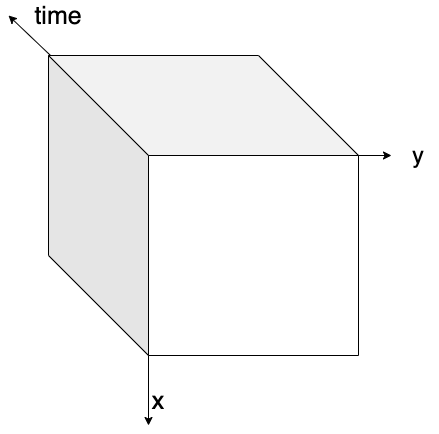

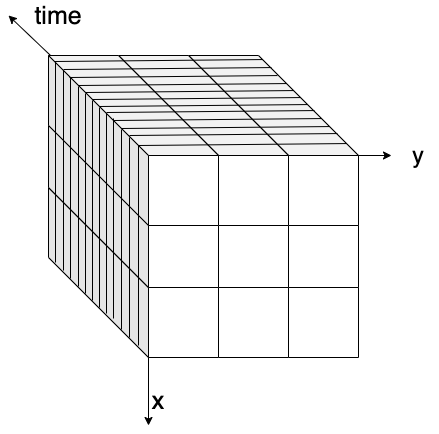

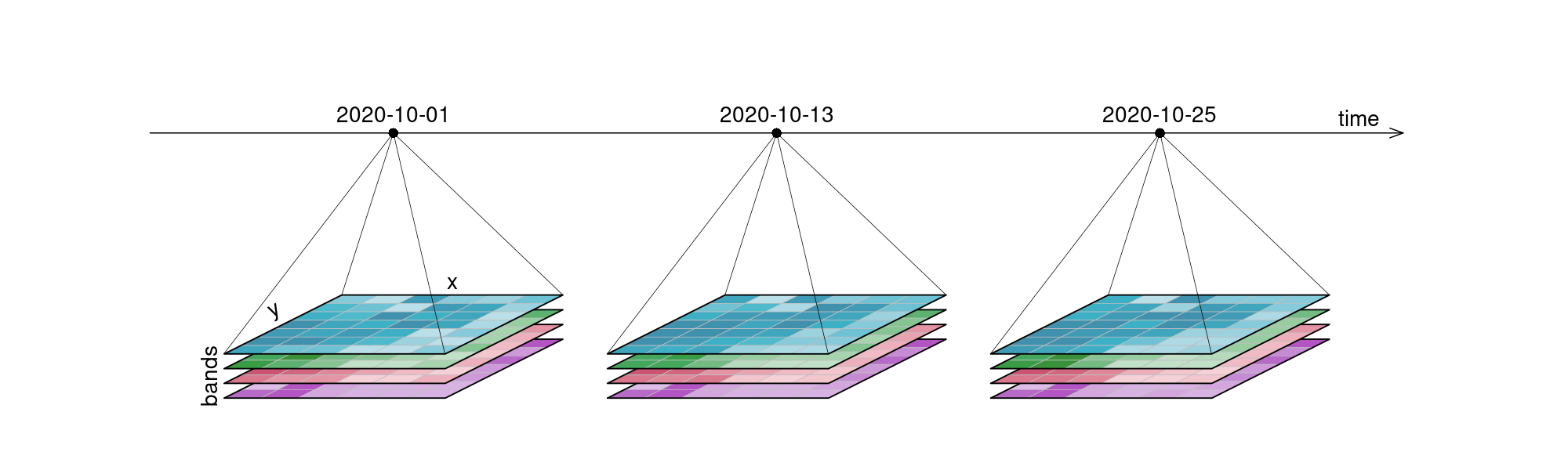

Python has become the lingua franca of EO processing through powerful libraries. Before diving into the details, let’s revisit data cubes and how we can represent them in Python. EO data cubes in Python are typically represented as labeled multidimensional arrays that integrate data values, coordinates, and metadata. Consider, for example, a 6x7 raster with 4 spectral bands collected over 3 time points. This structured representation allows efficient and intuitive access to complex EO datasets.

Fig. 1 An examplary raster datacube with 4 dimensions: x, y, bands and time.#

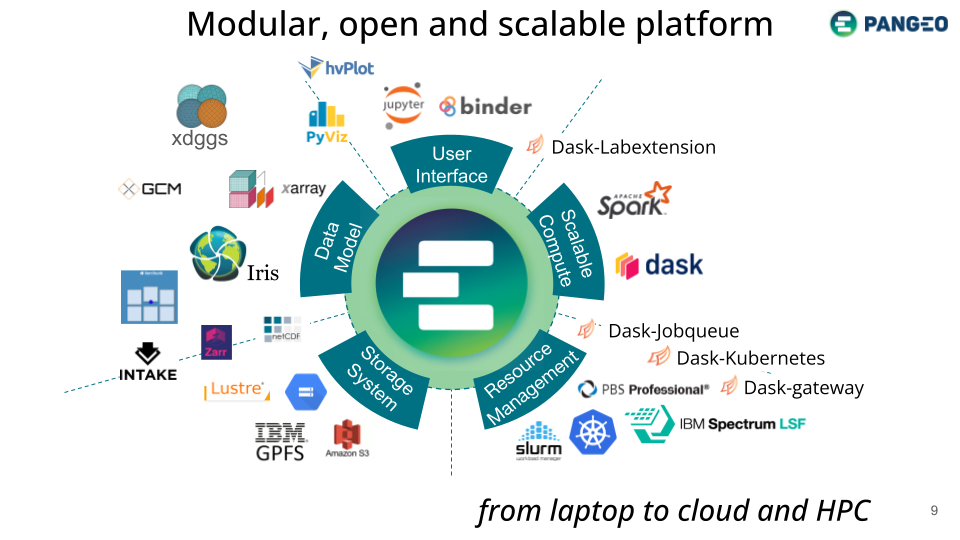

The demo below uses the Pangeo ecosystem to access and process data.

Note

The Pangeo ecosystem Pangeo is a Community-Driven Approach to Advancing Open Source Earth Observation Tools Across Disciplines.

The list of Python packages below is not exhaustive. Its purpose is mainly to draw a visual picture of the different components typically needed for Earth Observation workflows.

Data Models#

xarray → N-dimensional arrays (gridded data).

geopandas → Tabular vector data (points, lines, polygons).

shapely → Geometries & spatial operations.

pyproj → Coordinate systems & reprojection.

eopf-xarray → Extends xarray with EO Processing Framework methods.

Storage Solutions (I/O & Formats)#

rioxarray → GeoTIFFs + CRS handling.

rasterio → Raster I/O.

fiona → Vector I/O (GeoJSON, Shapefile).

Zarr / NetCDF (via xarray) → Cloud-native, chunked array storage.

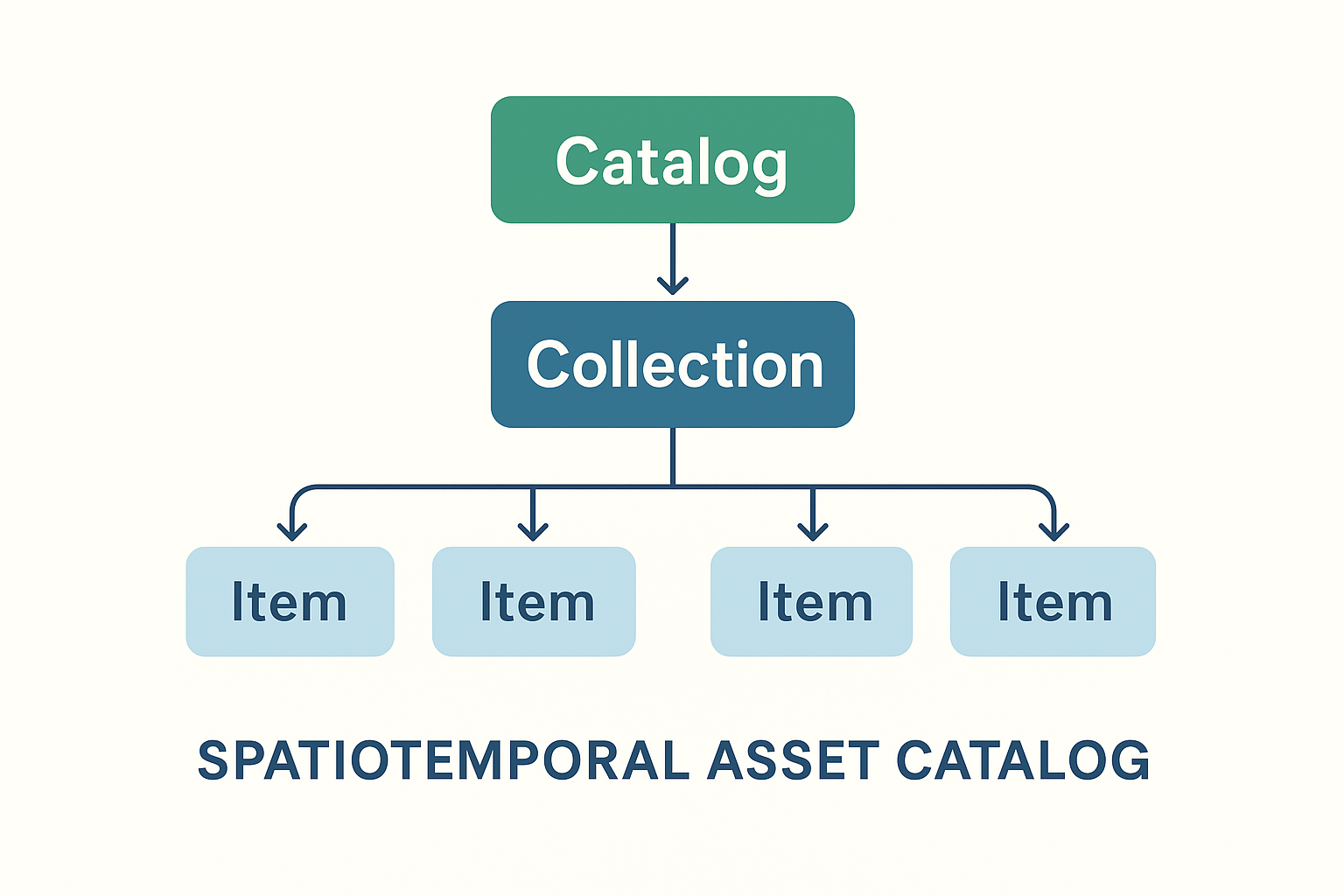

Catalogs & Metadata (optional)#

Catalogs are not strictly required — you can load files directly — but they become invaluable when dealing with large, multi-sensor, or cloud-hosted EO datasets.

pystac → STAC objects (Items, Collections, Catalogs).

sat-search → Search STAC APIs.

stackstac → Turn STAC items into xarray stacks.

odc-stac → Load STAC into xarray (optimized for EO).

Scalable Compute#

dask → Parallel/distributed computing.

pangeo stack → Dask + xarray ecosystem for scalable EO.

User Interfaces & Visualization#

hvplot → High-level, interactive plotting (works with xarray, geopandas, dask).

holoviews / panel → Dashboards and advanced UIs.

folium / ipyleaflet → Interactive maps in notebooks.

cartopy → Map projections & static plots.

Resource Management & Deployment (optional)#

Kubernetes / Dask Gateway → Manage compute clusters.

Pangeo Hub / JupyterHub → Multi-user access to scalable EO environments.

Data cubes and Lazy data loading with Xarray#

When accessing data through an API or cloud service, data is often lazily loaded. This means that initially only the metadata is retrieved, allowing us to understand the data’s dimensions, spatial and temporal extents, available spectral bands, and additional context without downloading the entire dataset.

Xarray supports this approach effectively, providing a powerful interface to open, explore, and manipulate large EO data cubes efficiently.

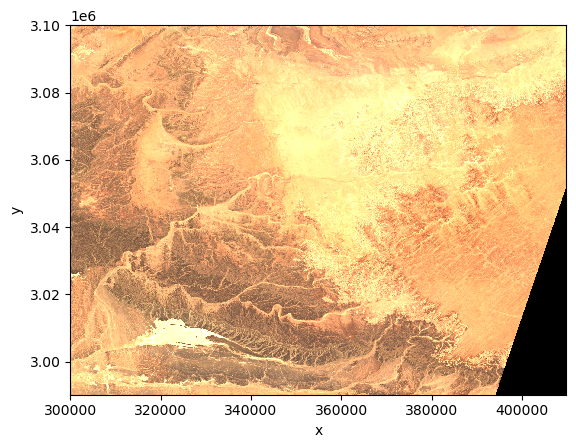

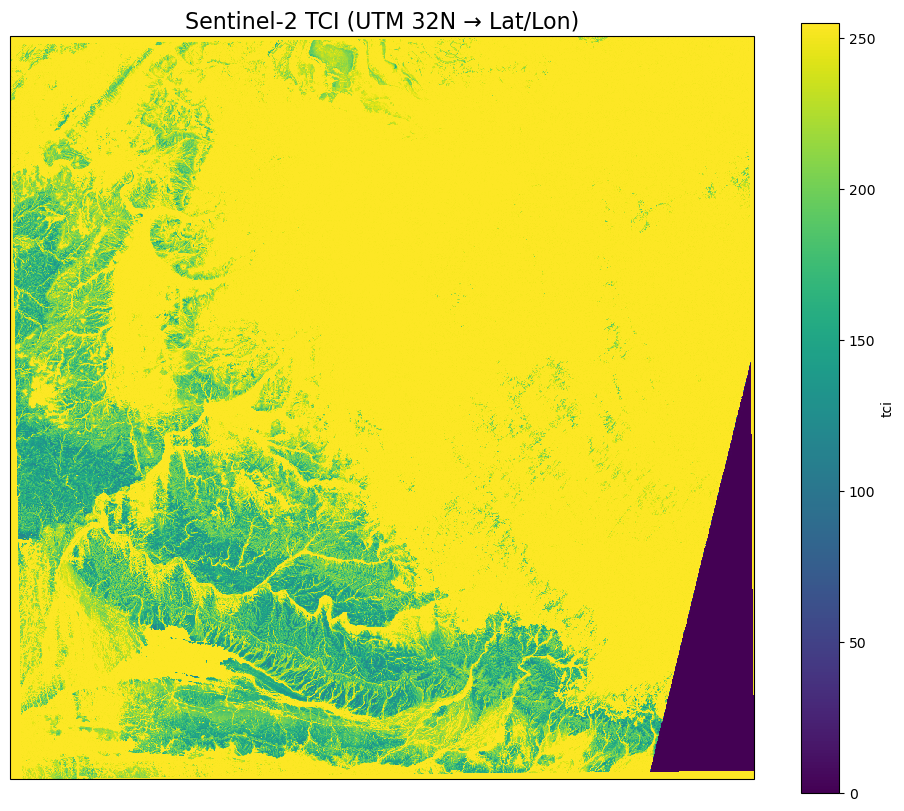

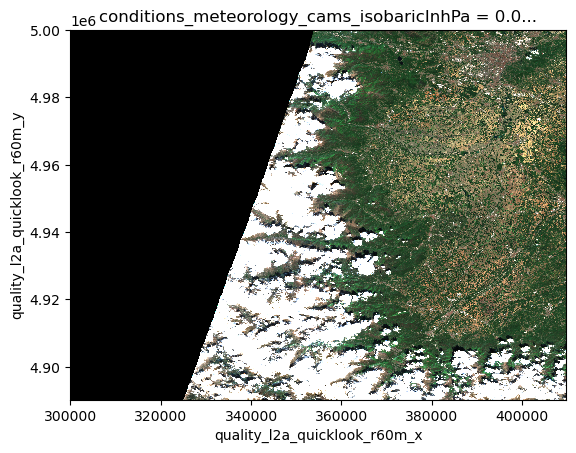

Let’s open an example dataset to explore these capabilities.

Note

xarray-eopf xarray-eopf is a Python package that extends xarray with a custom backend called “eopf-zarr”. This backend enables seamless access to ESA EOPF data products stored in the Zarr format, presenting them as analysis-ready data structures.

This notebook demonstrates how to use the xarray-eopf backend to explore and analyze EOPF Zarr datasets. It highlights the key features currently supported by the backend.

🐙 GitHub: EOPF Sample Service – xarray-eopf

📘 Documentation: xarray-eopf Docs

import xarray as xr

xr.set_options(display_expand_attrs=False)

<xarray.core.options.set_options at 0x1083ddb90>

path = (

"https://objects.eodc.eu/e05ab01a9d56408d82ac32d69a5aae2a:202505-s02msil2a/18/products"

"/cpm_v256/S2B_MSIL2A_20250518T112119_N0511_R037_T29RLL_20250518T140519.zarr"

)

ds = xr.open_datatree(path, engine="eopf-zarr", op_mode="native", chunks={})

ds

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B

Dimensions: ()

Data variables:

*empty*

Attributes: (2)<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*conditions<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 559kB Dimensions: (angle: 2, band: 13, y: 23, x: 23, detector: 5) Coordinates: * angle (angle) <U7 56B 'zenith' 'azimuth' * band (band) <U3 156B 'b01' 'b02' ... 'b11' 'b12' * detector (detector) int64 40B 8 9 10 11 12 * x (x) int64 184B 300000 305000 ... 410000 * y (y) int64 184B 3100020 3095020 ... 2990020 Data variables: mean_sun_angles (angle) float64 16B dask.array<chunksize=(2,), meta=np.ndarray> mean_viewing_incidence_angles (band, angle) float64 208B dask.array<chunksize=(13, 2), meta=np.ndarray> sun_angles (angle, y, x) float64 8kB dask.array<chunksize=(2, 23, 23), meta=np.ndarray> viewing_incidence_angles (band, detector, angle, y, x) float64 550kB dask.array<chunksize=(7, 5, 2, 23, 23), meta=np.ndarray>geometry- angle: 2

- band: 13

- y: 23

- x: 23

- detector: 5

- angle(angle)<U7'zenith' 'azimuth'

array(['zenith', 'azimuth'], dtype='<U7')

- band(band)<U3'b01' 'b02' 'b03' ... 'b11' 'b12'

array(['b01', 'b02', 'b03', 'b04', 'b05', 'b06', 'b07', 'b08', 'b8a', 'b09', 'b10', 'b11', 'b12'], dtype='<U3') - detector(detector)int648 9 10 11 12

array([ 8, 9, 10, 11, 12])

- x(x)int64300000 305000 ... 405000 410000

array([300000, 305000, 310000, 315000, 320000, 325000, 330000, 335000, 340000, 345000, 350000, 355000, 360000, 365000, 370000, 375000, 380000, 385000, 390000, 395000, 400000, 405000, 410000]) - y(y)int643100020 3095020 ... 2995020 2990020

array([3100020, 3095020, 3090020, 3085020, 3080020, 3075020, 3070020, 3065020, 3060020, 3055020, 3050020, 3045020, 3040020, 3035020, 3030020, 3025020, 3020020, 3015020, 3010020, 3005020, 3000020, 2995020, 2990020])

- mean_sun_angles(angle)float64dask.array<chunksize=(2,), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['angle'], 'dimensions': ['angle']}

- unit :

- deg

Array Chunk Bytes 16 B 16 B Shape (2,) (2,) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray - mean_viewing_incidence_angles(band, angle)float64dask.array<chunksize=(13, 2), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['angle', 'band'], 'dimensions': ['band', 'angle']}

- unit :

- deg

Array Chunk Bytes 208 B 208 B Shape (13, 2) (13, 2) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray - sun_angles(angle, y, x)float64dask.array<chunksize=(2, 23, 23), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['angle', 'y', 'x'], 'dimensions': ['angle', 'y', 'x']}

Array Chunk Bytes 8.27 kiB 8.27 kiB Shape (2, 23, 23) (2, 23, 23) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray - viewing_incidence_angles(band, detector, angle, y, x)float64dask.array<chunksize=(7, 5, 2, 23, 23), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['angle', 'y', 'x', 'detector', 'band'], 'dimensions': ['band', 'detector', 'angle', 'y', 'x']}

Array Chunk Bytes 537.27 kiB 289.30 kiB Shape (13, 5, 2, 23, 23) (7, 5, 2, 23, 23) Dask graph 2 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*mask<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*detector_footprint<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 482MB Dimensions: (y: 10980, x: 10980) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 88kB 300005 300015 300025 300035 ... 409775 409785 409795 * y (y) int64 88kB 3100015 3100005 3099995 ... 2990245 2990235 2990225 Data variables: b02 (y, x) uint8 121MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b03 (y, x) uint8 121MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b04 (y, x) uint8 121MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b08 (y, x) uint8 121MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>r10m- y: 10980

- x: 10980

- x(x)int64300005 300015 ... 409785 409795

array([300005, 300015, 300025, ..., 409775, 409785, 409795])

- y(y)int643100015 3100005 ... 2990235 2990225

array([3100015, 3100005, 3099995, ..., 2990245, 2990235, 2990225])

- b02(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 114.98 MiB 3.19 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b03(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 114.98 MiB 3.19 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b04(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 114.98 MiB 3.19 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b08(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 114.98 MiB 3.19 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 181MB Dimensions: (y: 5490, x: 5490) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 44kB 300010 300030 300050 300070 ... 409750 409770 409790 * y (y) int64 44kB 3100010 3099990 3099970 ... 2990270 2990250 2990230 Data variables: b05 (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray> b06 (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray> b07 (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray> b11 (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray> b12 (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray> b8a (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>r20m- y: 5490

- x: 5490

- x(x)int64300010 300030 ... 409770 409790

array([300010, 300030, 300050, ..., 409750, 409770, 409790])

- y(y)int643100010 3099990 ... 2990250 2990230

array([3100010, 3099990, 3099970, ..., 2990270, 2990250, 2990230])

- b05(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b06(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b07(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b11(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b12(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b8a(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 10MB Dimensions: (y: 1830, x: 1830) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 15kB 300030 300090 300150 300210 ... 409650 409710 409770 * y (y) int64 15kB 3099990 3099930 3099870 ... 2990370 2990310 2990250 Data variables: b01 (y, x) uint8 3MB dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray> b09 (y, x) uint8 3MB dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray> b10 (y, x) uint8 3MB dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>r60m- y: 1830

- x: 1830

- x(x)int64300030 300090 ... 409710 409770

array([300030, 300090, 300150, ..., 409650, 409710, 409770])

- y(y)int643099990 3099930 ... 2990310 2990250

array([3099990, 3099930, 3099870, ..., 2990370, 2990310, 2990250])

- b01(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [1830, 1830]

- proj:transform :

- [60.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -60.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 3.19 MiB 90.84 kiB Shape (1830, 1830) (305, 305) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b09(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [1830, 1830]

- proj:transform :

- [60.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -60.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 3.19 MiB 90.84 kiB Shape (1830, 1830) (305, 305) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray - b10(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'long_name': 'detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- long_name :

- detector footprint mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry). 0 = no detector, 1-12 = detector 1-12

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [1830, 1830]

- proj:transform :

- [60.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -60.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 3.19 MiB 90.84 kiB Shape (1830, 1830) (305, 305) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*l1c_classification<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 3MB Dimensions: (y: 1830, x: 1830) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 15kB 300030 300090 300150 300210 ... 409650 409710 409770 * y (y) int64 15kB 3099990 3099930 3099870 ... 2990370 2990310 2990250 Data variables: b00 (y, x) uint8 3MB dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>r60m- y: 1830

- x: 1830

- x(x)int64300030 300090 ... 409710 409770

array([300030, 300090, 300150, ..., 409650, 409710, 409770])

- y(y)int643099990 3099930 ... 2990310 2990250

array([3099990, 3099930, 3099870, ..., 2990370, 2990310, 2990250])

- b00(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u1', 'flag_masks': [1, 2, 4], 'flag_meanings': ['OPAQUE', 'CIRRUS', 'SNOW_ICE'], 'long_name': 'cloud classification mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry)'}

- dtype :

- <u1

- flag_masks :

- [1, 2, 4]

- flag_meanings :

- ['OPAQUE', 'CIRRUS', 'SNOW_ICE']

- long_name :

- cloud classification mask provided in the final reference frame (ground geometry)

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [1830, 1830]

- proj:transform :

- [60.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -60.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 3.19 MiB 90.84 kiB Shape (1830, 1830) (305, 305) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*l2a_classification<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 30MB Dimensions: (y: 5490, x: 5490) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 44kB 300010 300030 300050 300070 ... 409750 409770 409790 * y (y) int64 44kB 3100010 3099990 3099970 ... 2990270 2990250 2990230 Data variables: scl (y, x) uint8 30MB dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>r20m- y: 5490

- x: 5490

- x(x)int64300010 300030 ... 409770 409790

array([300010, 300030, 300050, ..., 409750, 409770, 409790])

- y(y)int643100010 3099990 ... 2990250 2990230

array([3100010, 3099990, 3099970, ..., 2990270, 2990250, 2990230])

- scl(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(915, 915), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x']}

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [5490, 5490]

- proj:transform :

- [20.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -20.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 28.74 MiB 817.60 kiB Shape (5490, 5490) (915, 915) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 3MB Dimensions: (y: 1830, x: 1830) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 15kB 300030 300090 300150 300210 ... 409650 409710 409770 * y (y) int64 15kB 3099990 3099930 3099870 ... 2990370 2990310 2990250 Data variables: scl (y, x) uint8 3MB dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>r60m- y: 1830

- x: 1830

- x(x)int64300030 300090 ... 409710 409770

array([300030, 300090, 300150, ..., 409650, 409710, 409770])

- y(y)int643099990 3099930 ... 2990310 2990250

array([3099990, 3099930, 3099870, ..., 2990370, 2990310, 2990250])

- scl(y, x)uint8dask.array<chunksize=(305, 305), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x']}

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [1830, 1830]

- proj:transform :

- [60.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -60.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

Array Chunk Bytes 3.19 MiB 90.84 kiB Shape (1830, 1830) (305, 305) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type uint8 numpy.ndarray

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*meteorology<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 4kB Dimensions: (latitude: 9, longitude: 9) Coordinates: isobaricInhPa float64 8B ... * latitude (latitude) float64 72B 28.01 27.89 27.77 ... 27.16 27.03 * longitude (longitude) float64 72B -11.03 -10.89 ... -10.05 -9.909 number int64 8B ... step int64 8B ... surface float64 8B ... time datetime64[ns] 8B ... valid_time datetime64[ns] 8B ... Data variables: aod1240 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> aod469 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> aod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> aod670 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> aod865 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> bcaod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> duaod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> omaod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> ssaod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> suaod550 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> z (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> Attributes: (7)cams- latitude: 9

- longitude: 9

- isobaricInhPa()float64...

- long_name :

- pressure

- positive :

- down

- standard_name :

- air_pressure

- stored_direction :

- decreasing

- units :

- hPa

[1 values with dtype=float64]

- latitude(latitude)float6428.01 27.89 27.77 ... 27.16 27.03

- long_name :

- latitude

- standard_name :

- latitude

- stored_direction :

- decreasing

- units :

- degrees_north

array([28.01 , 27.888, 27.766, 27.644, 27.522, 27.4 , 27.278, 27.156, 27.031])

- longitude(longitude)float64-11.03 -10.89 ... -10.05 -9.909

- long_name :

- longitude

- standard_name :

- longitude

- units :

- degrees_east

array([-11.034 , -10.893375, -10.75275 , -10.612125, -10.4715 , -10.330875, -10.19025 , -10.049625, -9.909 ]) - number()int64...

- long_name :

- ensemble member numerical id

- standard_name :

- realization

- units :

- 1

[1 values with dtype=int64]

- step()int64...

- long_name :

- time since forecast_reference_time

- standard_name :

- forecast_period

- units :

- nanoseconds

[1 values with dtype=int64]

- surface()float64...

- long_name :

- original GRIB coordinate for key: level(surface)

- units :

- 1

[1 values with dtype=float64]

- time()datetime64[ns]...

- long_name :

- initial time of forecast

- standard_name :

- forecast_reference_time

[1 values with dtype=datetime64[ns]]

- valid_time()datetime64[ns]...

- long_name :

- time

- standard_name :

- time

[1 values with dtype=datetime64[ns]]

- aod1240(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- aod1240

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 1240nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210216

- GRIB_shortName :

- aod1240

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 1240nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 1240nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - aod469(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- aod469

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 469nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210213

- GRIB_shortName :

- aod469

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 469nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 469nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - aod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- aod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210207

- GRIB_shortName :

- aod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - aod670(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- aod670

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 670nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210214

- GRIB_shortName :

- aod670

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 670nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 670nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - aod865(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- aod865

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 865nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210215

- GRIB_shortName :

- aod865

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 865nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Total Aerosol Optical Depth at 865nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - bcaod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- bcaod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Black Carbon Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210211

- GRIB_shortName :

- bcaod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Black Carbon Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Black Carbon Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - duaod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- duaod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Dust Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210209

- GRIB_shortName :

- duaod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- isobaricInhPa

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Dust Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Dust Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - omaod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- omaod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Organic Matter Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210210

- GRIB_shortName :

- omaod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Organic Matter Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Organic Matter Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - ssaod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- ssaod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Sea Salt Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210208

- GRIB_shortName :

- ssaod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Sea Salt Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Sea Salt Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - suaod550(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- suaod550

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Sulphate Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 210212

- GRIB_shortName :

- suaod550

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- ~

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Sulphate Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': '~'}

- long_name :

- Sulphate Aerosol Optical Depth at 550nm

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- ~

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - z(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- geopotential

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- z

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Geopotential

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 129

- GRIB_shortName :

- z

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- m**2 s**-2

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Geopotential', 'standard_name': 'geopotential', 'units': 'm**2 s**-2'}

- long_name :

- Geopotential

- standard_name :

- geopotential

- units :

- m**2 s**-2

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray

- Conventions :

- CF-1.7

- GRIB_centre :

- ecmf

- GRIB_centreDescription :

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

- GRIB_edition :

- 1

- GRIB_subCentre :

- 0

- history :

- 2025-05-18T20:19 GRIB to CDM+CF via cfgrib-0.9.10.4/ecCodes-2.34.1 with {"source": "../../mnt/data/eopf-conversion-kwr8p/S2B_MSIL2A_20250518T112119_N0511_R037_T29RLL_20250518T140519.SAFE/GRANULE/L2A_T29RLL_A042820_20250518T113246/AUX_DATA/AUX_CAMSFO", "filter_by_keys": {}, "encode_cf": ["parameter", "time", "geography", "vertical"]}

- institution :

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 2kB Dimensions: (latitude: 9, longitude: 9) Coordinates: isobaricInhPa float64 8B ... * latitude (latitude) float64 72B 28.01 27.89 27.77 ... 27.16 27.03 * longitude (longitude) float64 72B -11.03 -10.89 ... -10.05 -9.909 number int64 8B ... step int64 8B ... surface float64 8B ... time datetime64[ns] 8B ... valid_time datetime64[ns] 8B ... Data variables: msl (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> r (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> tco3 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> tcwv (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> u10 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> v10 (latitude, longitude) float32 324B dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray> Attributes: (7)ecmwf- latitude: 9

- longitude: 9

- isobaricInhPa()float64...

- long_name :

- pressure

- positive :

- down

- standard_name :

- air_pressure

- stored_direction :

- decreasing

- units :

- hPa

[1 values with dtype=float64]

- latitude(latitude)float6428.01 27.89 27.77 ... 27.16 27.03

- long_name :

- latitude

- standard_name :

- latitude

- stored_direction :

- decreasing

- units :

- degrees_north

array([28.01 , 27.888, 27.766, 27.644, 27.522, 27.4 , 27.278, 27.156, 27.031])

- longitude(longitude)float64-11.03 -10.89 ... -10.05 -9.909

- long_name :

- longitude

- standard_name :

- longitude

- units :

- degrees_east

array([-11.034 , -10.893375, -10.75275 , -10.612125, -10.4715 , -10.330875, -10.19025 , -10.049625, -9.909 ]) - number()int64...

- long_name :

- ensemble member numerical id

- standard_name :

- realization

- units :

- 1

[1 values with dtype=int64]

- step()int64...

- long_name :

- time since forecast_reference_time

- standard_name :

- forecast_period

- units :

- nanoseconds

[1 values with dtype=int64]

- surface()float64...

- long_name :

- original GRIB coordinate for key: level(surface)

- units :

- 1

[1 values with dtype=float64]

- time()datetime64[ns]...

- long_name :

- initial time of forecast

- standard_name :

- forecast_reference_time

[1 values with dtype=datetime64[ns]]

- valid_time()datetime64[ns]...

- long_name :

- time

- standard_name :

- time

[1 values with dtype=datetime64[ns]]

- msl(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- air_pressure_at_mean_sea_level

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- msl

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Mean sea level pressure

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 151

- GRIB_shortName :

- msl

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- Pa

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Mean sea level pressure', 'standard_name': 'air_pressure_at_mean_sea_level', 'units': 'Pa'}

- long_name :

- Mean sea level pressure

- standard_name :

- air_pressure_at_mean_sea_level

- units :

- Pa

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - r(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- relative_humidity

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- r

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Relative humidity

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 157

- GRIB_shortName :

- r

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- isobaricInhPa

- GRIB_units :

- %

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Relative humidity', 'standard_name': 'relative_humidity', 'units': '%'}

- long_name :

- Relative humidity

- standard_name :

- relative_humidity

- units :

- %

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - tco3(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- atmosphere_mass_content_of_ozone

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- tco3

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total column ozone

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 206

- GRIB_shortName :

- tco3

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- kg m**-2

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total column ozone', 'standard_name': 'atmosphere_mass_content_of_ozone', 'units': 'kg m**-2'}

- long_name :

- Total column ozone

- standard_name :

- atmosphere_mass_content_of_ozone

- units :

- kg m**-2

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - tcwv(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- lwe_thickness_of_atmosphere_mass_content_of_water_vapor

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- tcwv

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- Total column vertically-integrated water vapour

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 137

- GRIB_shortName :

- tcwv

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- kg m**-2

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': 'Total column vertically-integrated water vapour', 'standard_name': 'lwe_thickness_of_atmosphere_mass_content_of_water_vapor', 'units': 'kg m**-2'}

- long_name :

- Total column vertically-integrated water vapour

- standard_name :

- lwe_thickness_of_atmosphere_mass_content_of_water_vapor

- units :

- kg m**-2

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - u10(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- u10

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- 10 metre U wind component

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 165

- GRIB_shortName :

- 10u

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- m s**-1

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': '10 metre U wind component', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': 'm s**-1'}

- long_name :

- 10 metre U wind component

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- m s**-1

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray - v10(latitude, longitude)float32dask.array<chunksize=(9, 9), meta=np.ndarray>

- GRIB_NV :

- 0

- GRIB_Nx :

- 9

- GRIB_Ny :

- 9

- GRIB_cfName :

- unknown

- GRIB_cfVarName :

- v10

- GRIB_dataType :

- fc

- GRIB_gridDefinitionDescription :

- Latitude/Longitude Grid

- GRIB_gridType :

- regular_ll

- GRIB_iDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.141

- GRIB_iScansNegatively :

- 0

- GRIB_jDirectionIncrementInDegrees :

- 0.122

- GRIB_jPointsAreConsecutive :

- 0

- GRIB_jScansPositively :

- 0

- GRIB_latitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- 28.01

- GRIB_latitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- 27.031

- GRIB_longitudeOfFirstGridPointInDegrees :

- -11.034

- GRIB_longitudeOfLastGridPointInDegrees :

- -9.909

- GRIB_missingValue :

- 3.4028234663852886e+38

- GRIB_name :

- 10 metre V wind component

- GRIB_numberOfPoints :

- 81

- GRIB_paramId :

- 166

- GRIB_shortName :

- 10v

- GRIB_stepType :

- instant

- GRIB_stepUnits :

- 0

- GRIB_totalNumber :

- 0

- GRIB_typeOfLevel :

- surface

- GRIB_units :

- m s**-1

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'coordinates': ['number', 'time', 'step', 'surface', 'latitude', 'longitude', 'valid_time', 'isobaricInhPa'], 'dimensions': ['latitude', 'longitude'], 'long_name': '10 metre V wind component', 'standard_name': 'unknown', 'units': 'm s**-1'}

- long_name :

- 10 metre V wind component

- standard_name :

- unknown

- units :

- m s**-1

Array Chunk Bytes 324 B 324 B Shape (9, 9) (9, 9) Dask graph 1 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float32 numpy.ndarray

- Conventions :

- CF-1.7

- GRIB_centre :

- ecmf

- GRIB_centreDescription :

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

- GRIB_edition :

- 1

- GRIB_subCentre :

- 0

- history :

- 2025-05-18T20:19 GRIB to CDM+CF via cfgrib-0.9.10.4/ecCodes-2.34.1 with {"source": "../../mnt/data/eopf-conversion-kwr8p/S2B_MSIL2A_20250518T112119_N0511_R037_T29RLL_20250518T140519.SAFE/GRANULE/L2A_T29RLL_A042820_20250518T113246/AUX_DATA/AUX_ECMWFT", "filter_by_keys": {}, "encode_cf": ["parameter", "time", "geography", "vertical"]}

- institution :

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*measurements<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 0B Dimensions: () Data variables: *empty*reflectance<xarray.DatasetView> Size: 4GB Dimensions: (y: 10980, x: 10980) Coordinates: * x (x) int64 88kB 300005 300015 300025 300035 ... 409775 409785 409795 * y (y) int64 88kB 3100015 3100005 3099995 ... 2990245 2990235 2990225 Data variables: b02 (y, x) float64 964MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b03 (y, x) float64 964MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b04 (y, x) float64 964MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray> b08 (y, x) float64 964MB dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>r10m- y: 10980

- x: 10980

- x(x)int64300005 300015 ... 409785 409795

array([300005, 300015, 300025, ..., 409775, 409785, 409795])

- y(y)int643100015 3100005 ... 2990235 2990225

array([3100015, 3100005, 3099995, ..., 2990245, 2990235, 2990225])

- b02(y, x)float64dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'add_offset': -0.1, 'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u2', 'fill_value': 0, 'long_name': 'BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b02 492.3 nm', 'scale_factor': 0.0001, 'units': 'digital_counts'}

- dtype :

- <u2

- fill_value :

- 0

- long_name :

- BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b02 492.3 nm

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

- units :

- digital_counts

- valid_max :

- 65535

- valid_min :

- 1

Array Chunk Bytes 919.80 MiB 25.55 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray - b03(y, x)float64dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'add_offset': -0.1, 'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u2', 'fill_value': 0, 'long_name': 'BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b03 559.0 nm', 'scale_factor': 0.0001, 'units': 'digital_counts'}

- dtype :

- <u2

- fill_value :

- 0

- long_name :

- BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b03 559.0 nm

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :

- [10.0, 0.0, 300000.0, 0.0, -10.0, 3100020.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

- proj:wkt2 :

- PROJCS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 29N",GEOGCS["WGS 84",DATUM["WGS_1984",SPHEROID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7030"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6326"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,AUTHORITY["EPSG","8901"]],UNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9122"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","4326"]],PROJECTION["Transverse_Mercator"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",0],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-9],PARAMETER["scale_factor",0.9996],PARAMETER["false_easting",500000],PARAMETER["false_northing",0],UNIT["metre",1,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9001"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH],AUTHORITY["EPSG","32629"]]

- units :

- digital_counts

- valid_max :

- 65535

- valid_min :

- 1

Array Chunk Bytes 919.80 MiB 25.55 MiB Shape (10980, 10980) (1830, 1830) Dask graph 36 chunks in 2 graph layers Data type float64 numpy.ndarray - b04(y, x)float64dask.array<chunksize=(1830, 1830), meta=np.ndarray>

- _eopf_attrs :

- {'add_offset': -0.1, 'coordinates': ['x', 'y'], 'dimensions': ['y', 'x'], 'dtype': '<u2', 'fill_value': 0, 'long_name': 'BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b04 665.0 nm', 'scale_factor': 0.0001, 'units': 'digital_counts'}

- dtype :

- <u2

- fill_value :

- 0

- long_name :

- BOA reflectance from MSI acquisition at spectral band b04 665.0 nm

- proj:bbox :

- [300000.0, 2990220.0, 409800.0, 3100020.0]

- proj:epsg :

- 32629

- proj:shape :

- [10980, 10980]

- proj:transform :